Highlighting the rich history of the Byberry neighborhood of Northeast Philadelphia by activating four historic sites along or near the Poquessing Creek Trail through public programs and historic restoration and interpretation.

BYBERRY HALL: ROBERT PURVIS’ LEGACY

By Jack McCarthy, Project Director

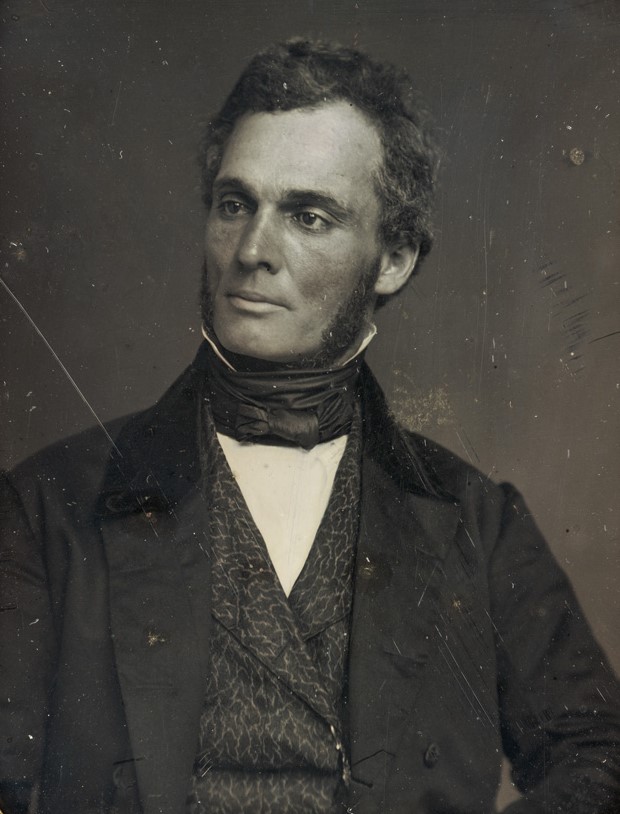

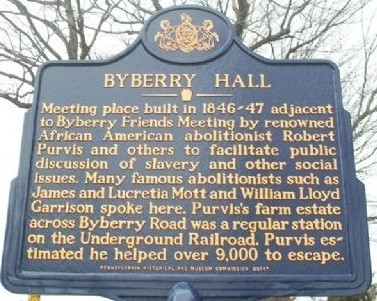

In 1844, Robert Purvis, a prominent thirty-four-year-old Black abolitionist and leading figure in the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia, moved with his wife and children to the village of Byberry in the far northern part of Philadelphia County. Purvis’ activism had put his life in danger in the racially charged, often violent city in the early 1840s and Byberry, a rural Quaker enclave some fourteen miles away, offered both a safe place for his family and a location where he could continue his Underground Railroad work more effectively. Three years after settling there, Purvis formed the Trustees of Byberry Hall and built Byberry Hall to serve as a community meeting place and center for his ongoing social activism.

Robert Purvis was born in 1810 in Charleston, South Carolina, to a white father who was a wealthy Scottish-born cotton broker and a mother of African descent who was a free woman of color. In 1819, the family moved to Philadelphia, where Robert would emerge as a leader of the city’s Black community. Wealthy, educated, and charismatic, Purvis was light skinned and could have easily passed for white, but chose to identify with his African heritage and work tirelessly for his people.

A well-known speaker and author, in 1838 Purvis wrote the influential pamphlet Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens Threatened with Disfranchisement, which urged the repeal of a new Pennsylvania constitutional amendment that removed the right to vote from free Blacks. Among his many high-profile affiliations, Purvis served as president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society from 1845-1850 and chairman of the General Vigilance Committee for the Underground Railroad from 1852-1857. Later in life he estimated that he had helped some 9,000 freedom seekers escape from slavery. He has sometimes been called the “Father of the Underground Railroad”.

In 1831, Purvis married Harriet Davey Forten, daughter of James Forten, who owned a successful sailmaking company and was one of Philadelphia’s most respected Black residents. An important activist in her own right, Harriet was one of the founders in 1831 of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, the nation’s first interracial abolition organization. Robert and Harriet would go on to have eight children and build a life of activism together, hosting many abolitionists and social reformers in their home in the city, and later in Byberry. These homes also served as important stops on the Underground Railroad.

Robert and Harriet were involved in the infamous events around the May 1838 opening of Pennsylvania Hall, the grand meeting hall built in downtown Philadelphia by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society to host abolitionist and other social reform activities. Resentful of the activities and mingling of races taking place in the building, an angry mob burned it to the ground shortly after its opening. One of the things that reportedly incensed the rioters was the sight of Robert and Harriet walking arm-in-arm into the building, which they mistook as a white man escorting a Black woman.

The Purvises were threatened again four years later in what came to be known as the Lombard Street Riots. For several days in August 1842, white mobs attacked Black people, homes, and institutions in the vicinity of the Purvis home on Lombard Street. Robert himself was a target of the rioters at one point, prompting him to send Harriet and the children to safety in Bucks County and to sit on the stairs of his home at night with a rifle on his knees in case of attack. Although he and his home were spared, the episode left Purvis disheartened, as he later wrote to a fellow abolitionist: “I know not where to begin . . . [in describing] . . . the wantonness, brutality, and murderous spirit, of the actors, in the late riots, nor of the apathy and inhumanity of the whole community—in regard to the matter—Press, Church, Magistrate, Clergymen, and Devils are against us.”

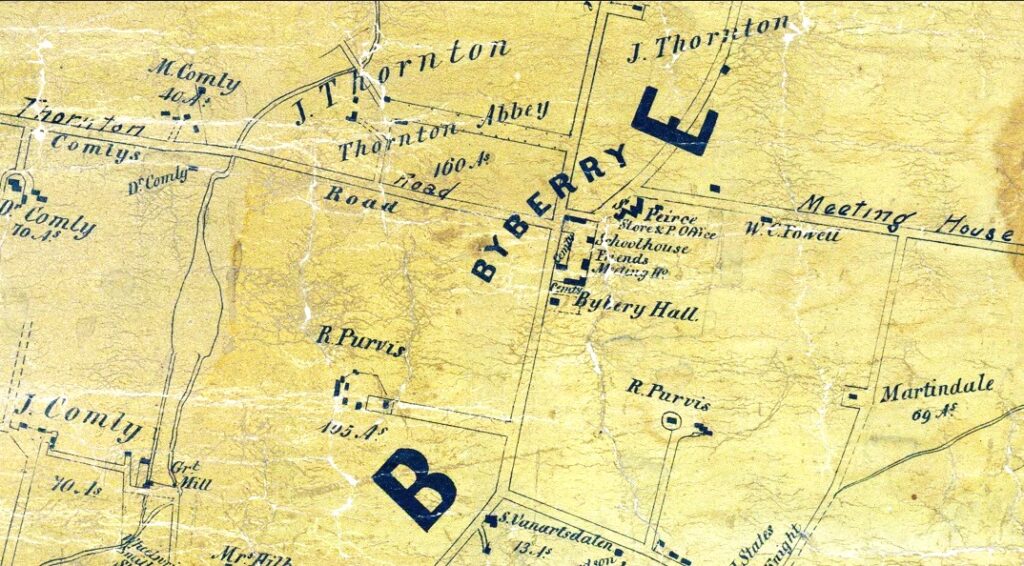

A year later, Robert and Harriet purchased a home and 105 acres of land in rural Byberry Township and moved there with their children in 1844. Their new home, stately Harmony Hall, was in the village of Byberry, just across the road from Byberry Friends Meeting. The congregation was founded in 1683 and moved in 1694 to the location it has occupied ever since, at the intersection of Byberry and Thorton Roads in what is now Far Northeast Philadelphia. The Purvis property was on either side of Byberry Road, with a large portion of it sitting adjacent to the Meeting property.

In 1847, Robert and Harriet sold a small parcel of their land adjacent to the Meeting property to the newly formed Trustees of Byberry Hall for $50. Robert was one of the three founding Trustees, along with Samuel Kirk and James Fields. Kirk was a member of Byberry Meeting; Fields was a Byberry resident but not a Meeting member.

As stipulated in the deed, the land was to be held by the Trustees “for the purpose of having a hall erected thereon to be dedicated to free discussion, to be independent of, and untrammeled by, any sect or party, to subserve the interest or caprice of no bigot, dogmatist, or tyrant, but in the fullest and freest sense to give ample scope and a fair field for the utterance of free speech.” Given Robert Purvis’ history of public activism and the fact that he and Harriet provided the land, it is probable that Robert was the initiator of the Byberry Hall project.

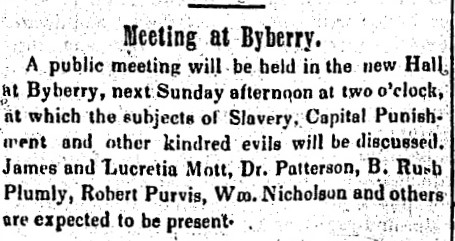

On July 15, 1847, the abolitionist newspaper The Pennsylvania Freeman announced the first public event to be held in the new hall: “A public meeting will be held in the new Hall at Byberry, . . . at which the subjects of Slavery, Capital Punishment and other kindred evils will be discussed. James and Lucretia Mott, Dr. Patterson, B. Rush Plumly, Robert Purvis, Wm. Nicholson and others are expected to be present.”

Two weeks later, The Pennsylvania Freeman reported on the meeting and the new hall:

[The] building was opened for the first time on that occasion, and . . . the house was quite filled. The exercises were conducted on the free-meeting principle [and] were very spirited, and seemed to give general satisfaction. . . . [The speakers] gave variety and life to the meeting. The various branches of moral reform were touched upon, but anti-slavery claimed especial attention. The privilege of plain speaking was freely exercised and the peculiar obstacles to the cause in and about Byberry were animadverted [i.e., critically remarked or commented] upon without fear or favor. . . . The hall … is a very neat edifice, made of stone and plaster, and … reflects much credit upon those who got it up. It is built on a corner of the farm belonging to Robert Purvis, and adjoins the grounds of Byberry Friends Meeting House; being within a very short distance of that building. It is large enough to accommodate about 300 persons.”

The Pennsylvania Freeman reported on meetings at Byberry Hall periodically in the ensuing years, as the building hosted such famous speakers as Lucretia Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, Susan B. Anthony, and Purvis himself. A spirited meeting was held on October 18, 1850, to discuss local response to passage a few weeks earlier of the federal Fugitive Slave Act. On October 31, 1850, The Pennsylvania Freeman published Purvis’ report on the meeting, which he prefaced by noting that “I send [this report]. . . , hoping that elsewhere and everywhere, among freedom’s loving friends an equally bold and manly determination to resist the bill of abominations will be made.” Thirty-eight attendees at the meeting signed a strongly worded denunciation of the new law, vowing to ignore it. The statement read in part:

The undersigned citizens of the township of Byberry, Philadelphia County, . . . have, upon mature reflection, agreed . . . That we will utterly disregard the monstrous and inhuman requirements of said bill, viewing them as subversive of the principles of Christianity—the laws of God and our common humanity—and will not be deterred, come what may to our “reputation, property, or lives,” . . . and we will as heretofore open our doors for the reception and protection of every flying bond man, who may make his escape from the prison-house of bondage.

In addition to Robert and Harriet Purvis, many prominent local Quakers signed the declaration. While not Quakers themselves, the Purvises were part of the Byberry Quaker community and participated in many of its activities and organizations. They sent their children to the Byberry Meeting elementary school and when their sons William and Robert Jr. died young—William in 1857 at age twenty-four; Robert in 1862 at twenty-seven-–they buried them in the Meeting’s cemetery. In the 1870s, when the Meeting needed to expand the cemetery, Robert and Harriet sold the Meeting a portion of their land adjacent to the cemetery.

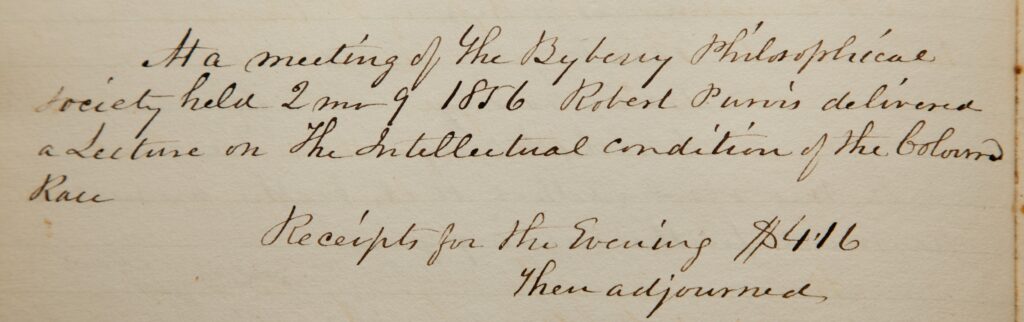

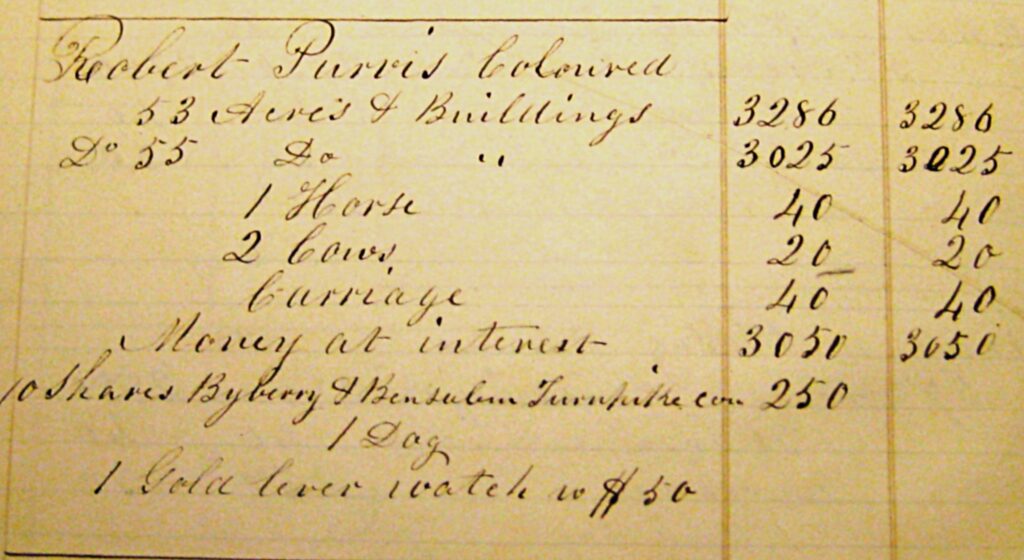

Robert was a member of the Byberry Library Company, founded in 1794, and the Byberry Philosophical Society, founded in 1829, both comprised primarily of members of Byberry Meeting. He checked out numerous Library Company books in the 1850s and 1860s and gave several talks at Philosophical Society meetings, which were held in Byberry Hall. The society minutes note one such talk on February 2, 1856, when Purvis “delivered a Lecture on the Intellectual condition of the Coloured Race.” He was also very much a gentleman farmer in this period, with his livestock and produce winning prizes at local agricultural fairs.

While generally accepted in the Byberry community, Robert Purvis was subjected to episodes of racism and discrimination. He was called by racial slurs at a local farm show and there was an effort to expel him from the Bensalem Horse Company, based in nearby Bucks County (he owned five horses) because he was Black. The most public episode was an attempt in 1853 to prevent his children, who had done their elementary studies at Byberry Friends School, from attending the local public secondary school, relegating them instead to a school for Black children in the nearby village of Mechanicsville. Purvis’ letter to the Byberry tax collector was published in the Boston-based abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, in December 1853:

The proscription and exclusion of my children from the Public School [is] illegal . . . I have borne this outrage ever since the innovation upon [i.e., change from] the usual practice of admitting all the children of the Township into the Public Schools, and at considerable expense, have been obliged to obtain the services of private teachers to instruct my children, while my school tax is greater, with a single exception, than that of any other citizen of the township.

I was informed by a pious Quaker director . . . that a school in the village of Mechanicsville, was appropriate for “thine.” The miserable shanty … is, as you know, the most flimsy and ridiculous sham.

Purvis threatened to withhold payment of his school taxes and eventually prevailed. His children were allowed to attend the regular local public school.

Byberry Hall went through a series of tangled ownership changes around this time. The Trustees of Byberry Hall apparently went into debt and on August 1, 1853, the building was sold at sheriff’s sale for an unpaid debt of $509.40. The buyers were Robert Purvis himself and Henry Bowman, one of the signers of the 1850 declaration against the Fugitive Slave Law. On March 14, 1854, Bowman sold his one-half ownership in the property to Purvis for $240.

On March 24, 1854, Purvis and his wife sold the property for $500 to Emmor Comly, James Thorton, and Joshua Newbold, acting as Trustees for the Byberry Hall Association. This new Association seems to have been established as a successor to the original 1847 Trustee group that had apparently dissolved when the building was sold at sheriff’s sale in 1853. Although not one of the trustees of the new Association himself, Robert Purvis was a stockholder and active member of the organization, serving as its president for a period in the late 1850s and 1860s.

Robert attended meetings of the Byberry Hall Association through late 1871 but appears to have had no involvement in the organization after that. By 1872 he and Harriet were living in Washington DC, where Robert was serving as a commissioner of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, chartered by Congress in 1865 to collect deposits from newly emancipated communities. With the Civil War over and slavery abolished, their focus shifted. In October 1872 they sold their main property in Byberry and the following year moved back to downtown Philadelphia. Harriet died in 1875 at age sixty-five and Robert in 1898 at age eight-seven.

Byberry Hall remained in public use into the early 2020s. Owned by the Trustees of Byberry Hall Association, it was made available for community activities, from local elections to entertainment events, through the mid-twentieth century. From 1968 to 2021, it was rented out as a martial arts studio. In 1980, the Byberry Hall Association formally dissolved and ownership of the hall was transferred to Byberry Friends Meeting.

After the martial arts studio closed, the Meeting engaged the services of a preservation architect to develop a restoration plan for the building and help secure grants to begin a multi-stage process of renovating it into a public meeting place once again. As a stakeholder in the Poquessing Trail of History project, Byberry Friends Meeting is helping to shape public programming around the rich history of the Byberry Hall and developing plans to have it serve as a local history center as well as community meeting place.

Sources Consulted:

But One Race: The Life of Robert Purvis, by Margaret Hope Bacon, State University Press of New York, 2007.

Byberry Library collections, Byberry Friends Meeting.

Friends Historical Library collections, Swarthmore College.

Map Collection, Historical Society of Frankford.

The Pennsylvania Freeman, accessed online via the Center for Research Libraries.