Highlighting the rich history of the Byberry neighborhood of Northeast Philadelphia by activating four historic sites along or near the Poquessing Creek Trail through public programs and historic restoration and interpretation.

NOT FORGOTTEN: BYBERRY TOWNSHIP AFRICAN AMERICAN BURIAL GROUND

By Jack McCarthy, Project Director

Like much of early Philadelphia Black history, there are many gaps and undocumented aspects to the story of the Byberry Township African American Burial Ground. Established by Byberry Friends (Quaker) Meeting in 1780 as a final resting place for free Blacks and people of color in the Byberry area, the small burial plot was actively used into the mid-nineteenth century, after which it became dormant and largely forgotten until efforts to honor it began in the 2010s.

To understand the history of the Burial Ground, it is necessary to know the history of enslavement in Byberry, which was primarily, although not exclusively, a Quaker community in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Quakers would emerge in the early nineteenth century as one of the most vocal groups in the fight against slavery, but for much of the eighteenth century it was a divisive issue for them. While many Quakers actively campaigned against slavery, others were slave owners, including several in Byberry.

There are no known accounts or descriptions of the early Black residents of Byberry themselves, either enslaved or free. With a few exceptions, we do not know their names or practically anything about them, other than who owned them and where some of them were buried. One of the best sources of information on enslavement and burial practices for Blacks in early Byberry is Isaac Comly’s article “Sketches of the History of Byberry in the County of Philadelphia,” published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1827. Comly’s ancestors were among the early Quaker settlers of Byberry in the 1680s and his family were longtime members of Byberry Friends Meeting.

Comly writes that enslavement was introduced to the Byberry area around 1720:

From about 1720, we find, divers [sic] of the most opulent persons in and near Byberry, and some of them distinguished members of [Byberry Friends] meeting, were concerned [i.e., involved] in the purchase of negroes brought to Philadelphia from the coast of Africa. The number of slaves appears to have increased till about 1758, when Friends issued a formidable protest against slavery. From that time the number rapidly decreased. It does not appear that more than two or three members of Byberry meeting persisted in holding slaves.

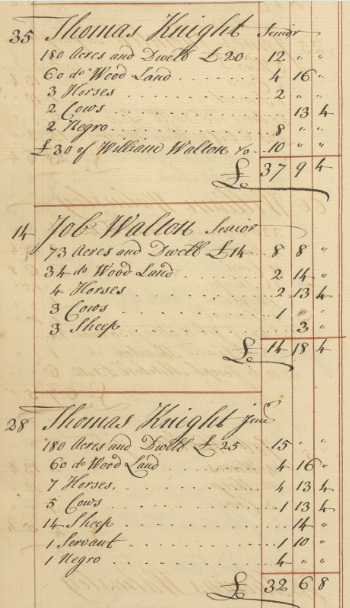

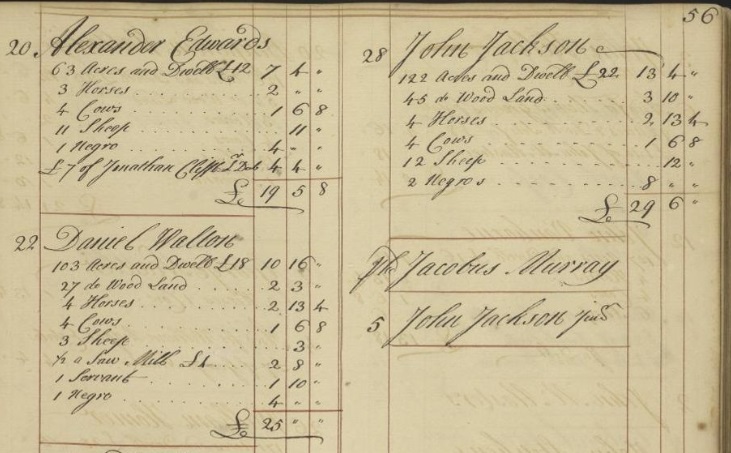

A 1767 Philadelphia County tax record reveals that Comly slightly underestimated the number of Quaker slave owners in Byberry. Of the seventy-nine recorded taxpayers in Byberry that year, eight were slaveholders, five of whom were members of Byberry Meeting. The eight slaveholders held a total of eleven enslaved Africans, as Blacks referred to themselves in the eighteenth century.

Detail from the Byberry section of the 1767 Philadelphia County tax record entitled “The particulars of each person’s estate, as appears by the township and ward assessors’ returns.” This page shows Thomas Knight Senior holding two enslaved people and Thomas Knight Junior holding one. Both were members of Byberry Friends Meeting. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

Comly states that prior to 1780, enslaved Africans were buried on their owners’ properties when they died:

The negroes were formerly buried in the orchards belonging to their masters. There was also a cemetery for them on lands late of William Walmsley, where it appears thirty or forty were interred. In 1780, Friends purchased a lot of Thomas Townsend, for a negro burying ground, and the practice of burying on private property was discontinued.

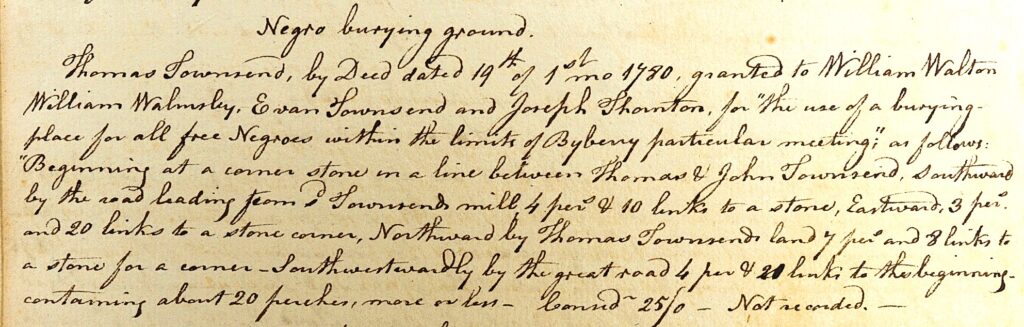

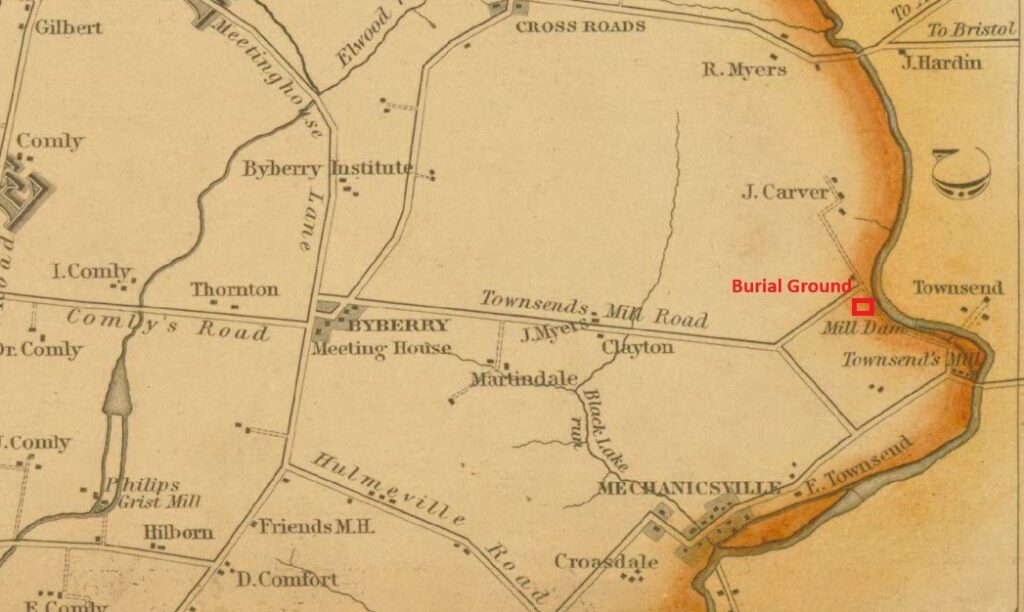

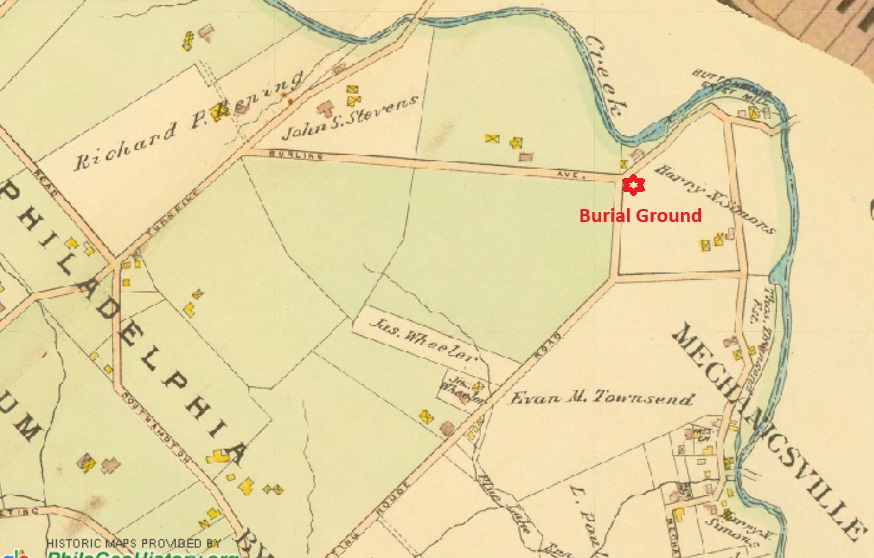

In February 1780, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed an “Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” in the state. It was apparently in response to the coming law that Byberry Friends Meeting decided to establish a burial ground specifically for “all free Negroes” in Byberry. On January 19, 1780, Thomas Townsend deeded a small plot of his land near Poquessing Creek, about a mile from the Meeting House, to four fellow members of the Meeting for “the use of a burying place for all free Negroes within the limits of Byberry particular meeting.” In later years, as the plot was transferred to subsequent Meeting members, the wording was changed to “all free Negroes or people of Color.”

Isaac Comly died in 1847 and twenty years later his “Sketches” and other writings were incorporated into a full-length book entitled A History of the Townships of Byberry and Moreland, in Philadelphia, PA, written by Comly’s nephew Joseph C. Martindale. In his preface to the 1867 book, Martindale noted that he and his colleagues collected additional materials and “spent much time and labor in hunting up old manuscripts.” It is presumably based on these additional sources that Martindale, in writing about “the burying place for the blacks,” states that “The record says the first person buried there was ‘Jim,’ a negro belonging to Daniel Walton.” What record Martindale is referring to is unknown; Jim is not mentioned in Comly’s 1827 “Sketches.”

Daniel Walton was a Quaker who operated a sawmill along the Poquessing Creek in Byberry. Jim is probably the “Negro” listed among Walton’s taxable possessions in the 1767 tax record (see below). Although the Comly and Martindale accounts seem to indicate that many people were interred in the Black Burial Ground, Jim is the only one whose name is known; all the others remain anonymous. However, Martindale notes that the 1743 inventory of the estate of an unnamed deceased local Quaker included “A negro woman Phillis . . . and one negro boy Wallis.” Perhaps Phillis and Wallis lived long enough in Byberry to be interred in the Burial Ground as well.

Comly notes in his “Sketches” that most local Quaker slave owners began freeing their slaves in the mid-eighteenth century, that by 1781 there were only three enslaved people remaining in Byberry, and that by the 1820s slavery had “entirely vanished” from the area. He also notes that the 1810 census showed that of a total of 767 people living in Byberry Township, thirty-three were Black. All, or almost all, of the latter must have been free, given the developments Comly reported over the previous half century in Byberry.

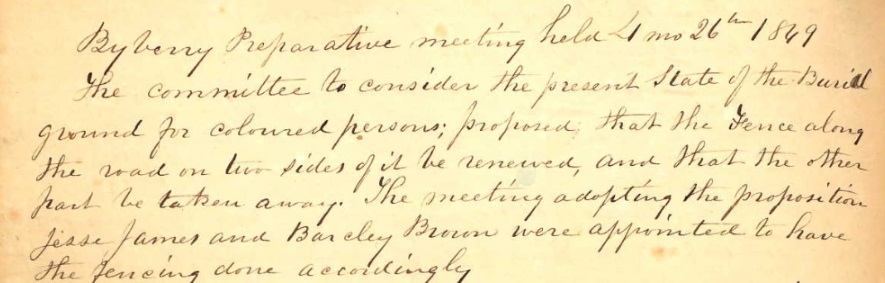

The minutes of Byberry Friends Meeting reveal that the Meeting actively maintained the Burial Ground into the mid-nineteenth century and that burials apparently continued at that time. The minutes for April 26, 1849, note that “The committee to consider the present State of the Burial ground for coloured persons” recommended repairs to the fence surrounding the plot, while the following month, on May 24, 1849, the minutes record that the work was completed and that four Meeting members “were appointed to have the care of the Burial Ground for coloured persons, and the admitting of internments therein.”

Martindale, in his History published eighteen years later, writes that:

The graveyard for colored persons, . . . situated in the eastern part of Byberry, is still kept for that purpose. Some years since a portion of this yard was plowed up, and most of the “little mounds” were levelled with the earth around, so that the exact spot where many of this race were buried can no longer be seen. . . . Of late years, more care has been taken of this place, and it is now kept in good order by Byberry Meeting.

This care apparently did not last into the twentieth century. In 1901, a new, revised edition of Martindale’s book was published, in which the editor added the following footnote to Martindale’s description: “This graveyard was converted into farmland about twenty-five years ago [c.1876], all the mounds being levelled with the ground.” Over time, the plot became increasingly abandoned and forgotten, remaining that way through most of the twentieth century and into the early twenty-first.

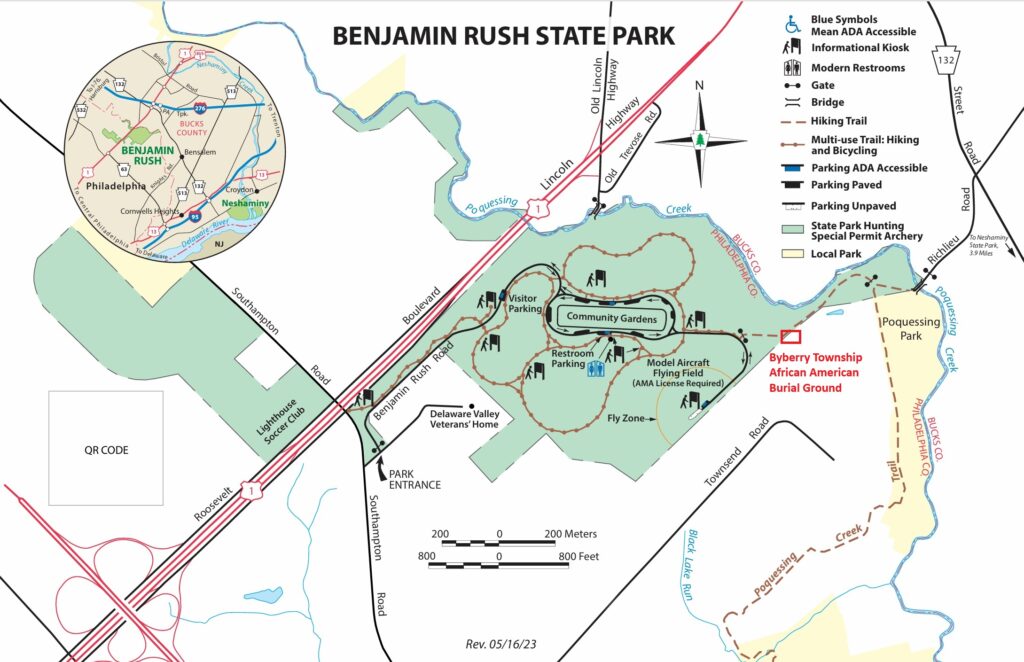

In 1975, Benjamin Rush State Park was created in the northeastern part of Byberry. The Burial Ground sat immediately adjacent to, but just outside, the boundaries of the park, at the intersection of the former Burling Avenue and Townsend and Meeting House Roads. These roads would eventually be stricken from city plans and become walking paths.

Around the time the state park was created, the City of Philadelphia began to convert tracts of land near the park into commercial and light industrial use. As part of these plans, the city wanted to include the small Burial Ground parcel, which was still owned by Byberry Friends Meeting and still largely neglected. In 1980, two hundred years after the Meeting originally created it, the Trustees of Byberry Meeting sold the small burial plot to the city and it became part of a larger parcel sold for commercial development. The plot itself was not developed, however, as it sat in a remote, wooded area on the outer edge of the commercial property, just a few feet from state park land.

The Burial Ground remained mostly forgotten until the 2010s, when local historians and members of Byberry Meeting began to discuss its fate. Historical researcher Joe Menkevich successfully nominated the site to the city Historic Register in 2015, and in the early 2020s the newly formed Society to Preserve Philadelphia African American Assets approached the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia about restoring and honoring the site. Together, the Society and Alliance secured grant funding and partnered with interested organizations to develop plans for preserving and interpreting the site, now called Byberry Township African American Burial Ground.

In 2024, the Burial Ground became one of four historic sites in Byberry included in Preservation Alliance’s grant-funded Poquessing Trail of History project. As part of the project, the Alliance has engaged CHplanning, a Black-led landscape architecture firm, to further develop restoration and interpretation plans for the site. The Alliance is seeking funding to implement those plans. In another key development, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources approved plans for the Burial Ground to be officially incorporated into Benjamin Rush State Park. This small sacred space will now become public land and hopefully will be restored and appropriately honored in time for the celebration of the nation’s 250th anniversary in 2026.

Sources Consulted

- “Sketches of the History of Byberry in the County of Philadelphia,” by Isaac Comly, published in Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Vol. II, 1827.

- Available online at: Comly–Sketches-Byberry_1827.pdf.

- A History of the Townships of Byberry & Moreland in Philadelphia, PA., by Joseph Martindale, T. Ellwood Zell, 1867; New & Revised Edition, edited by Albert W. Dudley, George W. Jacobs & Co., 1901.

- The 1901 edition is available on the Internet Archive: A history of the townships of Byberry and Moreland

- Byberry Monthly Meeting records and Comly-White family papers, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College

- Philadelphia County Tax 1767, “The particulars of each person’s estate, as appears by the township and ward assessors’ returns,”. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

- Map of the County of Philadelphia byCharles Ellett 1843, and Atlas of the 23rd, 35th & 41st Wards of the City of Philadelphia by J. L. Smith, 1910. Map Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.

- Available online at: Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network.

- Nomination of the Burying Place For All Free Negroes or People of Color within Byberry Twp to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, submitted by Joe Menkevich, 2015. Philadelphia Historical Commission.

- Interpretation Plan for Byberry Township African American Burial Ground, prepared by Society for the Preservation of Philadelphia African American Assets and Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, 2024. Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia.

Thank you to Society to Preserve Philadelphia African American Assets board member Jacqueline Wiggins for her input on this article.