Highlighting the rich history of the Byberry neighborhood of Northeast Philadelphia by activating four historic sites along or near the Poquessing Creek Trail through public programs and historic restoration and interpretation.

THE ORIGINAL PEOPLE: THE LENAPE ON THE POQUESSING

By Jack McCarthy, Project Director

Jeremy Johnson, Delaware Tribe of Indians Cultural Education Director

Gianna Barone, Delaware Tribe of Indians Cultural Education Generalist

The Lenape, whose name means “The People” in their own language, were known among fellow Native Nations as the “Grandfathers” who inhabited the greater Delaware Valley area for some 16,000 years before Europeans began arriving in the early seventeenth century. Part of a broader group of Indigenous people with familial bonds and similar dialects that stretched from what is now southern New York to northern Delaware, the Lenape lived in central and southern New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, and northern Delaware, an area they call “Lenapëkòkink” (Lenape homeland). They spoke the Unami dialect and inhabited the east and west sides of the river they call “Lenapewihittuk,” which the English later named the Delaware River.

The Lenape were established along the many creeks that fed into the Delaware River, where they built dwellings, practiced their traditions and ceremonies, and hunted, fished, and farmed. One such creek was the Poquessing, which today forms the northern boundary of Philadelphia with Bucks County and runs through Byberry in Northeast Philadelphia. The Poquessing—meaning “place of mice” in Unami —is one of several creeks in the area that are still known by their Lenape names, including Pèmikpeka (Pennypack Creek) – meaning “where the water is flowing” – three miles to the south, and Nishanèk (Neshaminy Creek) – meaning “two creeks” – four miles to the north.

Contact between the Lenape and Europeans began in the early seventeenth century when the Dutch began exploring the Delaware River and setting up trading posts in the 1610s. In 1638 Swedes established the colony of New Sweden and began settling in the greater Delaware Valley with their compatriots the Finns. The Dutch took control from the Swedes in 1655, then the English from the Dutch in 1664. The Lenape established peaceful relations with all these groups (a few violent incidents notwithstanding), based on trade and agreements they forged with the Europeans on use of Lenape lands.

But there were fundamental misunderstandings. The European concept of “owning” land was foreign to the Lenape. They construed the treaties they signed with Europeans as granting the latter certain rights to use of the land, not ownership of it in perpetuity. Such misunderstandings would be an ongoing point of contention between the Lenape and the early settlers.

We do not have any surviving personal first-hand accounts from Lenape people themselves in this period. Theirs was an oral, unwritten culture; teachings and beliefs were passed down by word of mouth. Written reports from European observers describe the Lenape in great detail— where they lived, their physical appearance, their customs and practices—but there is very little from the Lenape perspective. Swedish engineer Peter Lindestrom surveyed the New Sweden colony in 1654-1655 and kept a detailed journal of his observations of the Lenape along the Delaware River. One of his entries notes their settlements along the creeks that fed into the river, using phonetical spellings for Poquessing, Pennypack, and other waterways:

[S]ix different places are settled, under six sachems or chiefs, each one commanding his tribe or people under him, . . . [there] being several hundred men strong, under each chief, counting women and children, . . . As for instance [at] Poaetquessingh, Pemickpacka, Wickquaquenscke, Wickquakonick, which are situated on the [Delaware] river, but Passajung and Nittabakonck are situated up at the Menejackse [Schuylkill] River.

By this time, the Lenape were suffering greatly from diseases introduced by the Europeans for which they had no immunity. Rampant sickness, together with losses due to the encroaching effects of colonialism, severely reduced Lenape numbers in the Delaware Valley over the course of the seventeenth century. Only a few thousand remained in the area by the latter part of the century.

Intensive European settlement of the Lenape region that would become Pennsylvania began with English Quakers, members of the Religious Society of Friends, in the early 1680s. In March 1681, the King of England granted William Penn, an English nobleman and prominent Quaker, a large tract of land west of the Delaware River. Penn arrived in his new province in October 1682 and formally established the Colony of Pennsylvania and its three original counties: Philadelphia, Bucks, and Chester.

True to his Quaker beliefs and his vision for Pennsylvania as a “Holy Experiment” where people of all faiths could live in peace and practice their religions freely, Penn was intent on treating the Lenape fairly, including compensating them for their land. While he did so honorably for the most part, and his relations with the Lenape were warm and respectful, there would be serious points of contention.

Tradition has it that soon after his arrival in Pennsylvania in fall 1682, Penn met with Lenape sachems at Shackamaxon on the Delaware River in Philadelphia, where they signed a treaty that formed the basis of their peaceful relations and Penn’s settlement of the colony. The event may or may not have actually occurred; there is no known documentary evidence of it. But as depicted in the famous painting by artist Benjamin West done some ninety years later, the treaty at Shackamaxon has become an enduring part of the legacy of Penn and the Lenape. According to legend, Tamanend, a powerful, respected sachem, signed the treaty with Penn.

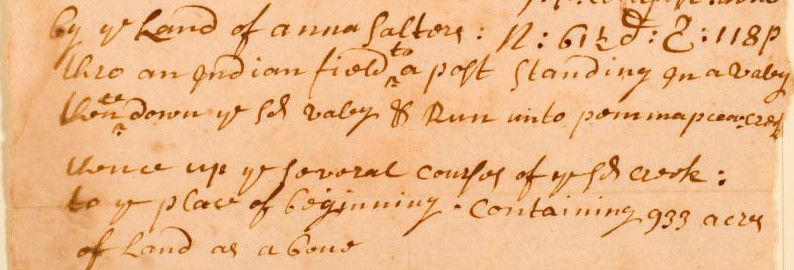

The documentary evidence that does exist suggests that what really formed the basis of Penn’s arrangements with the Lenape was a series of deeds signed on June 23, 1683, in which he purchased large tracts of land from various sachems. In one such deed, Tamanend and another local sachem, Metamequan, sold Penn all the land between Pennypack and Neshaminy Creeks, which included the Poquessing Creek watershed. The deed, now in the Pennsylvania State Archives, reads as follows:

WE, TAMAMEN and METAMEQUAN this 23d day of the 4th month, called June* in the year according to the English account 1683 for us our heirs and Assignes doe freely Graunt and dispose of all our Lands Lying betwixt and about Pemmapecka and Neshamineh Creeks and all along Neshemineh’s Creek to WILLIAM PENN Proprietary and Governor of Pensilvania, etcetera, his heirs and Assigns for Ever for the consideration of so much Wampum and other goods as he the said William Penn shall be pleased to give unto us.

*Note: until 1752, England and its colonies used the Julian, or “Old Style” calendar, in which the year began on March 25th. June would have been the fourth month of the year in 1683. Also note that English spellings of Lenape names—whether people, places, or creeks—varied widely in written documents.

Tamanend and Metamequan signed by making their marks at the bottom of the deed, which also includes the note: “Indians Present: Kuppape, Menaney, Katemus, Aphautess. Shockhuppo.”

Despite initial goodwill on both sides, disputes inevitably arose. Nicolas More, a prominent English settler and Penn confidant whose extensive Manor of Moreland lands later became Upper and Lower Moreland Townships, the latter adjacent to Byberry and within the Poquessing watershed, wrote to Penn in late 1684 that: “The Indians are Mutch displeased at our English settling upon their Land . . . saying that William Penn hath deceived them not paying for what he bought of them.”

Several of the English Quaker families who came to Pennsylvania with William Penn in fall 1682 settled in what became Byberry, on the northern edge of Philadelphia County, some fourteen miles up the Delaware River from the new city of Philadelphia. The name is derived from Bibury, a village in England from which some of the settlers emigrated. Isaac Comly, a descendant of an early Byberry family, wrote “Sketches of the History of Byberry in the County of Philadelphia,” which was published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1827. Comly notes that the Lenape were very helpful to the early Quaker settlers:

The first settlers had much difficulty to encounter, particularly in regard to a supply of provisions. The Indians near them treated them with kindness: they occasionally furnished such eatables as they could spare, and instructed the newcomers to raise corn, beans, and pumpkins.

Comly describes several specific instances of the Lenape aiding their new neighbors: “Giles Knight dwelt about six weeks by the side of an old log, near the banks of the Poquesink. The Indians then instructed him in the erection of a wigwam, in which he resided till he raised a small log house.” In another instance, when an early settler left on a long journey to procure wheat for planting:

“[H]is wife, child, and a small boy were left at home, upon what he thought a sufficient supply of provision for their support until his return; but some unforeseen hindrances kept him longer on the journey than was expected, and unfortunately the only cow they had, and upon whose milk they made much calculation for sustenance, got into the swamp and died. The poor woman by this accident was reduced to great difficulty, and concluded she must apply to some Indians not far distant, for assistance; she accordingly took the children, and went to their settlement. The Indians treated her with much kindness, furnished her and the children with victuals, and taking off the little boy’s trowsers, they filled them with corn for her to carry home for their further supply.

Byberry Friends Meeting, the Quaker congregation established in 1683, moved in 1694 to its current location at present-day Byberry and Thornton Roads, where it built a cemetery and a meeting house. Comly notes that “among those first interred were two Indian squaws, . . . whose graves are under [a] large cedar tree in the centre of the yard.” In 1742 the Meeting built a stone wall around the one-acre burial ground, which it continues to maintain as part of its five-acre historic property.

While relations between the early Byberry settlers and the Lenape were apparently friendly and supportive, by the early eighteenth century the growing European population—mostly Quakers but also some Baptists and Anglicans—had forced the Lenape out of Byberry to areas to the north and west. As the local settlers monopolized the land the Lenape lost access to the fresh water and food sources that sustained them and had to leave.

Following the death of William Penn in England in 1718, unscrupulous practices by his two sons and their agent James Logan deprived the Lenape of a large part of the remaining homeland to which they had moved. In 1737, the three arranged the infamous “Walking Purchase” that defrauded the Lenape out of some 1,200 square miles of land in northeastern Pennsylvania.

Most Lenape were gone from Byberry by this time, but Comly recounts that well into the late eighteenth century a small clan would return to the area every year for several months. They had moved to New Jersey, where more lands were still available to the Lenape, but returned to Byberry each spring and stayed on Thomas Walmsley’s property, bordering the Poquessing Creek in an area that is now on the west side of Roosevelt Boulevard, directly across from Benjamin Rush State Park:

Until about the year 1791, it had for a number of years been the custom for a part of a tribe of Indians from . . . New Jersey, to the number of twelve or fifteen, to visit Byberry every spring, where they were allowed by Thomas Walmsley to occupy one of his orchards. Upon their arrival they immediately employed themselves in erecting new wigwams, or repairing the old ones, and settled themselves comfortably for the summer. They . . . occupied a part of their time in making wooden trays, barn shovels, bowls, ladles, etc. of white poplar and in fabricating baskets of different descriptions and sizes. . . . Their natural taste for hunting had not been much diminished by their intercourse with the whites, and much of the time of the men was passed in roaming through the woods, fields, and about the hedges with their guns and bow and arrows in search of game. They were also fond of angling [fishing].

This little colony, . . . were not without an implied leader. The eldest appeared to be the patriarch, and old Indian Caleb, as he was familiarly called, stood at the head of the little community, and exercised his influence over it with apparent mildness, but at the same time with much of that dignity, so uniformly observed in the aboriginal sons of our forests.

Isolated groups such as this notwithstanding, the vast majority of the Lenape were forced out of the region and undertook a long, tortured journey westward, settling far from their ancestral lands, only to be displaced some years later and forced to move again. This process unfolded for over 130 years until the Lenape finally were able to settle permanently on new Tribal lands, mostly in Oklahoma, although some ended up in Wisconsin and Ontario.

While there is little physical trace of the Lenape in the Byberry area today, their legacy lives on in the names they gave local creeks and in the pathways they created that later became major roads, the latter including Frankford and Bustleton Avenues. Frankford Avenue, which parallels the Delaware River about a mile inland, was originally a Lenape path, strategically placed on high ground where the creeks it crossed stopped being tidal—close enough for convenient access to the river but far enough away to not be subject to its tidal fluctuations.

In the seventeenth century, the English began referring to the Lenape as the “Delaware” and many Lenape themselves would eventually adopt this name. Today, two of the three federally recognized Lenape Tribes in the United States use Delaware in their name: Delaware Tribe of Indians, based in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and Delaware Nation in Anadarko, Oklahoma. The Delaware Tribe of Indians is one of the stakeholder groups in the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia’s Poquessing Trail of History project. Tribal representatives are helping to shape and share with the public the stories of their ancestors in Byberry that will be highlighted in the project.

Sources Consulted

- Geographia Americae; with an account of the Delaware Indians, based on surveys and notes made in 1654-1656, by Peter Lindestrom. Published in 1925 by the Swedish Colonial Society.

- Available on Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/geographiaameric00lind.

- Description of the province of New Sweden: Now called, by the English, Pennsylvania, in America. Originally published in 1702.

- Available on Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/descriptionofpro00holm/mode/2up.

- “Sketches of the History of Byberry in the County of Philadelphia,” by Isaac Comly, published in Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Vol. II, 1827.

- Available online at: Comly–Sketches-Byberry_1827.pdf.

- Pennsylvania Archives, Selected and Arranged from Original Documents in the Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, Volume I, Published 1852. Pages 62-68 include transcriptions of “Indian Deeds.”

- Available on Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniaarch01harruoft/pennsylvaniaarch01harruoft/page/n1/mode/1up

- Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn, by Jean Soderlund, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

- Holme family papers, Historical Society of Frankford

- This collection includes both digital copies and original documents from a collection made available to the Historical Society of Frankford by descendants of the Holme family in 2008-2009. The family allowed HSF to digitally photograph the entire collection, then donated select items to HSF while retaining the originals of the bulk of the collection.

- Delaware Tribe of Indians, Culture and Language webpages: https://delawaretribe.org/culture-and-language/.

Many thanks to Pennsbury Manor Site Director Doug Miller for his knowledgeable input on this essay and to Friends of Northeast Philadelphia History board member Fred Moore for sharing his expertise on original archival sources documenting Lenape history in the area.